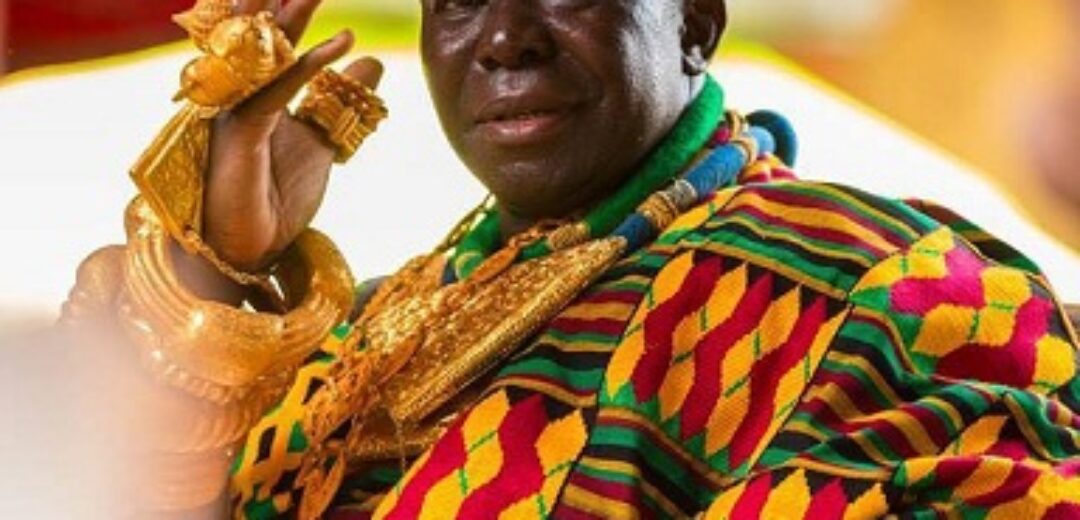

“The Asantehene’s Enduring Legacy: A Power Beyond Constitutional Bounds”

In a provocative essay by Douglas Peters argues that the Asantehene’s authority is not derived from Ghana’s constitution or government, but from a rich history that predates colonialism and modern statehood.

Douglas Peters contends that attempts to reduce the Asantehene to the level of “just another paramount chief” ignore the complexities of customary law, tradition, and the institution’s enduring influence.

GHANA DID NOT CREATE THE ASANTEHENE — AND NO REGIONAL GRIEVANCE CAN REDUCE HIM…

To those who insist on dragging the Asantehene down to the level of “just another paramount chief,” let us have an honest conversation—one rooted in history, law, and reality, not envy dressed up as constitutionalism.

Yes, Ghana is a constitutional republic.

But Ghana did not begin in 1992.

And power did not start with the Fourth Republic.

The Asantehene’s authority was not donated by Accra, licensed by Parliament, or manufactured by the Constitution.

His power predates colonialism, survived imperial war, negotiated coexistence with the British Crown, outlived independence, and remains fully operational in modern Ghana. Ghana did not crown the Asantehene. Ghana met him—and wisely chose accommodation over denial.

That single fact already separates him from every argument being made.

The Constitution is often quoted selectively to make emotional points. Article 270 of the 1992 Constitution does not “equalize” chiefs. It guarantees chieftaincy as it exists under customary law and usage.

That phrase is fatal to the claim that all traditional authorities are equal in rank, scope, or influence. Customary law does not flatten history. It preserves hierarchy.

Under customary law—long before colonialism—the Asantehene was never a paramount chief. He does not gazette as one today because he does not belong in that category.

A paramount chief presides over a traditional area. The Asantehene presides over a confederacy of traditional areas. He sits above paramountcy, not beside it.

This is not semantics. It is structure.

The Asantehene creates paramountcies. He has done so from pre-colonial times to the present day. Over seventy-seven paramount chiefs currently owe their stools to the Golden Stool, and more continue to be created.

More importantly, those same paramount chiefs can be destooled by the Asantehene.

No paramount chief in Ghana creates other paramount chiefs. No paramount chief receives allegiance from fellow paramount chiefs. No paramount chief sits atop an empire of stools. The Asantehene does all three.

That alone ends the argument.

The Chieftaincy Act, 2008 (Act 759) does not contradict this reality; it protects it. The Act deliberately defers to customary law in determining rank, allegiance, and jurisdiction. It does not impose artificial equality.

The state does not manufacture chiefs; it recognizes institutions already legitimated by history. Ghana’s courts have repeatedly affirmed this principle, holding that customary hierarchy—not administrative convenience—determines traditional authority.

This is also why the Asantehene has what no ordinary chief has: his own official seal, a structured traditional bureaucracy, and permanent state security stationed at Manhyia Palace.

The Ghana Police Service does not permanently guard palaces for aesthetics. That deployment is an acknowledgment that the Asantehene’s person is a matter of national stability. His safety is not a regional concern; it is a national one.

So when the Inspector-General of Police honours the Asantehene with a parade, or visits Manhyia during Akwasidae, this is not a republic bowing to monarchy. It is a modern state recognizing a pre-existing power whose moral authority still stabilizes millions of citizens.

To complain that other paramount chiefs do not receive similar treatment is to misunderstand influence itself. Influence is not allocated by fairness. It is accumulated by history, structure, continuity, and relevance. Equality before the law does not mean equality of legacy.

The tired claim that “Ghana is not a monarchical state” misses the point entirely. Article 276 bars chiefs from active partisan politics; it does not silence them, reduce them, or strip them of their civilizational weight.

Ghana rejected monarchy as a system of government, not as a repository of indigenous authority. The republic did not abolish kingship; it constitutionalized its limits.

That is why the Asantehene speaks on international platforms, engages institutions like the World Bank and IMF, receives presidents and global leaders at Manhyia, and is accorded diplomatic courtesies even outside Ghana, including the use of state aircraft when national interest demands it.

He does not do so as a rival to the President, but as Ghana’s most powerful symbol of indigenous legitimacy and soft power—something elections cannot manufacture.

What truly unsettles some people is not constitutional principle, but the uncomfortable visibility of relevance. The Asantehene’s continued prominence exposes a hard truth: some institutions command authority not because the state permits them to, but because history refuses to let them die.

So no, the Asantehene is not equal to a paramount chief.

He stands above that category altogether.

He was not made by the republic.

The republic inherited him.

And no amount of regional agitation, selective constitutional quotation, or rhetorical resentment will rewrite centuries of settled reality.

History is not democratic.

And it does not apologize.